Funding research! A funders or donor’s intent relates to the purposeful state of mind behind the act of giving. The desire and hope that their the gift will contribute to achieve a greater community good is often philanthropist’s underlying intent. The same can be said about the community’s willingness to give or support a cause.

When considering how we measure impact from medical research, do we place enough emphasis on intent? It should be about balance, but is intent being outweighed by spill-over benefits, institutional drivers, business strategies and individual needs?

It is likely that when most people think of medical research they think of cures, new treatments, diagnostics, better health services and outcomes. They believe this is the intent of funding medical research.

These same people fund medical research through taxes that in 2017 provided more than $877 million to fund health and medical research via the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the more recently established Medical Research Futures Fund (MRFF). Many of these people will also make donations to medical research charities, providing further financial support.

Donors may know little about health and medical research beyond their intent. They often make emotional decisions, entrusting their giving to organisations and researchers who have greater medical research knowledge and experience. Their motives are not about revenues that are normally the drivers for universities and other publicly funded research organisations (PFRO’s) where the research is undertaken.

On the basis of intent, I often start my presentations by reminding researchers that they are normally not the intended recipients of philanthropy, but rather that they are entrusted to deliver a greater community good. Grants are awarded to help achieve a ‘purpose’ that outlines the intent of a Foundation and those that have contributed to it.

We in turn must remember that researchers are employees of institutions, not Foundations and that there is a greater funding and policy ecosystem that needs to be considered.

Education is Australia’s third largest export market generating up to $28 billion in 2016-17. Much of this amount is generated through international fee-paying students, where Australia’s global reputation plays a significant role in attracting higher fee-paying students. Australian universities rank highly on international tables where significant indicators are publication (30%) and citation (30%) rates. These rankings are used for marketing purposes and can attract up to about one third of annual student enrolments. Translation and knowledge transfer (2.5%) impacts have little influence on these rankings.

The medical research sector is a major contributor to publications and university rankings. Whilst it is important for the nation to have a strong, vibrant and sustainable education sector the benefits are not directly aligned with the community’s intent and may be considered spill-over benefits with significant academic value.

The culture and KPIs in many PFROs are built upon the ‘publish or perish’ dogma that underpins their business models and influences researchers who need to consider not only the potential for career progression, but the ability to remain employed. Research outputs (publications) have become the necessary primary intent of the researcher taking priority over translational research opportunities that may compete with time and resources.

Revenue is the primary driver for Publicly Funded Research Organisations

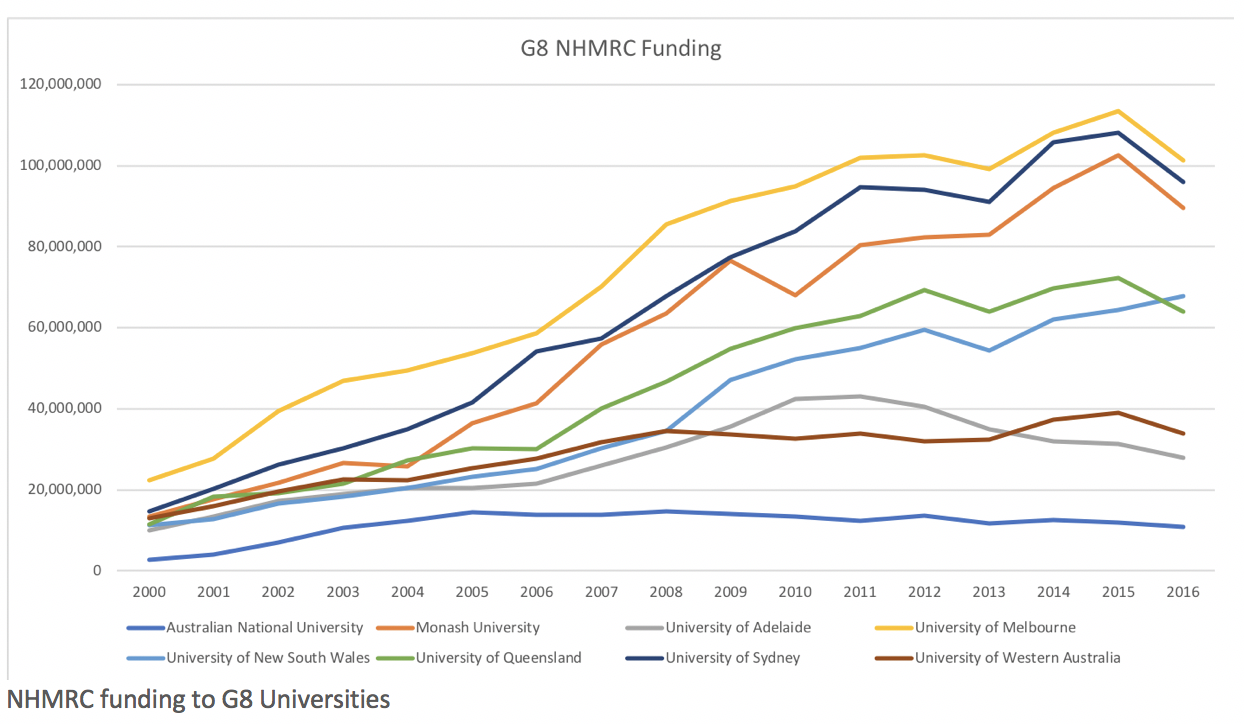

The underlying culture is not only about revenues from fee paying students, but also from other sources including government, research grants, industry and philanthropic sources. The NHMRC is the largest funder of research with significant funds provided annually for project grants and other support. It is interesting to note that development grants awarded in 2017 (commencing in 2018) totalled $13.8 million dollars. This is approximately 1.6% of the amount awarded in project grants that is directed towards advancing earlier discoveries and translation.

There are some recent changes to Research Block Grant (RBG) funding, the way impact is assessed in the Australian Research Council’s Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA), changes to the NHMRC’s grant funding program being introduced and new opportunities from the Medical Research Futures Fund (MRFF), including the Horizons programs that have potential to help move culture and assist translation.

Research from project grants is of interest to many publishers of scientific journals. This fits well with the PFRO business model where publications are a marketing tool and external funding for biomedical research is directed. It should be noted that publications as a KPI and measure in league tables is also inherently flawed. There are numerous articles highlighting the problem with reproducibility in leading scientific journals that infamously made news across the scientific community when Amgen was NOT able to reproduce more than 80% of papers. It begs the question, “is quality about headlines, the importance of findings or the robustness of the science”?

With the research grants funding the research who is funding translation? Government provides additional financial support to PFROs through a variety of funding mechanisms. However, it has not historically provided dedicated resources to translation, engagement and commercialisation. The PFROs must fund translational activities which are required for translation. With notable exceptions these are seen to be expense centres, not income generators.

Are revenues actually prioritised over community benefits?

Some PFROs invest in translation and have established internal capability and capacity, including technology transfer offices; others provide minimal and ineffective resources and some have none at all. Where insufficient resources are available to assist with translation there is little opportunity to deliver on the its intent.

There needs to be more consideration around aligning the expectations of funders with funding recipients if we want to improve translation and the return on investment from research to communities.

If translation and commercial outcomes are the predominant way via which the community accesses the benefits of the research it supports, shouldn’t it be an important consideration of allocating funding?

One argument is that translation and commercial outcomes don’t drive significant revenues and that resources in this area are an expense. Some PFROs make business decisions about the need, opportunity and resources provided based on revenues received from translation or commercialisation. An alternative view is that the revenue is provided upfront when a grant with ‘intent’ is offered with an expectation that pathways to deliver community benefits will naturally be supported and are in place.

By accepting funding is there a social contract to prioritise intent?

We need to be careful about introducing metrics and tipping the scales too far the other way. For instance, the outcomes from biomedical research often require commercialisation and investors who can help advance the discoveries towards developing new medicines, vaccines, diagnostics and devices which are then of benefit to the community. A basic measure of patents filed is poor, it is quantitative, not qualitative, and doesn’t reflect upon the value of patents which can lead to resource wastage. Including other individual metrics such as invention disclosures, patents granted, spin-off companies and licensing agreements can be helpful but on their own can mask issues along the translational pathway including where the chain may be broken.

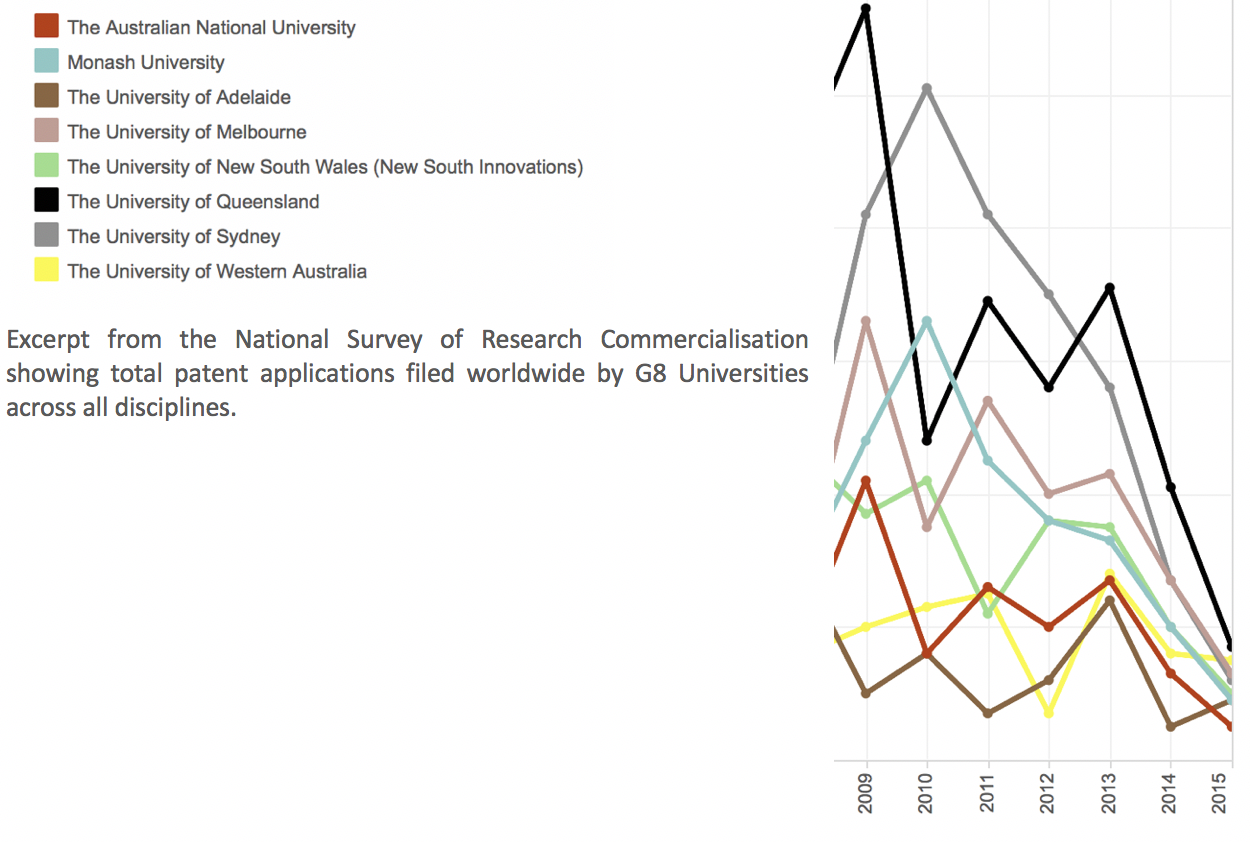

Looking at patents and trends together with other indicators around commercialisation and the level of internal capability and capacity can help identify organisations that may be more supportive of translation and commercialisation.

Although it currently only includes data up to 2015, the National Survey of Research Commercialisation (NSRC) includes numerous metrics and may provide insight to funders about what questions to ask of institutions and possibly the culture relating to commercialisation. It also highlights a potential downward trend.

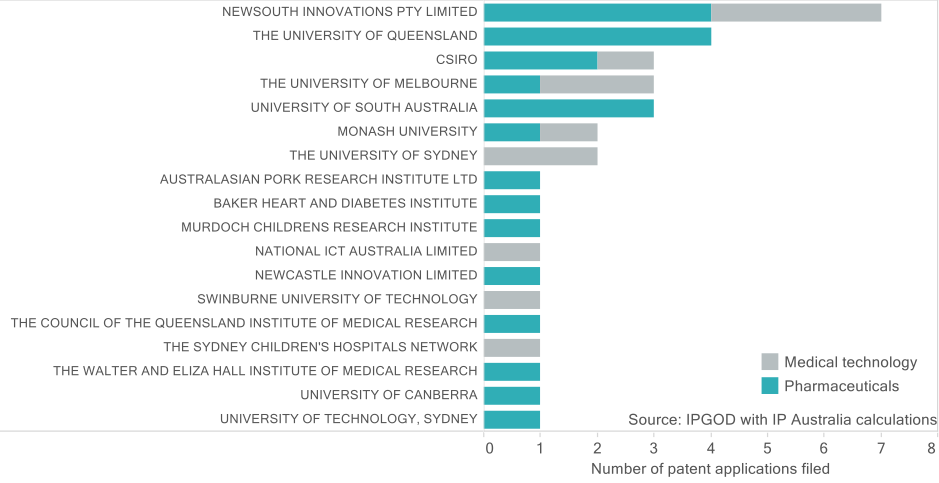

IP Australia kindly provided a note to 2018 IP Report showing filings by Australian PFRO applicants in 2017, in pharmaceutical and medical technologies. Whilst comparing patent filings in any particular year with grant revenues in any particular year is problematic it is interesting to consider the level of patent filing with the funds received. It is not unreasonable to anticipate that institutions who receive more funding for research to file more patents.

Basic science is required to make the discoveries in the first place, but letting the discoveries whither on the vine is a problem. Moving too far towards translation could leave little to translate. Balance is key!

Can funding research have unintended consequences?

Funding research can have the potential for harm through unintended consequences. Over funding of early career research places without providing support for mid-career progression and other skills could leave mid-career researchers stranded. Early career researchers may provide cost-effective solutions for research, but new strategies are needed to support researchers as their careers progress.

More complex, however, is the concept that medical discoveries have already been made, but never delivered benefits as the translational support wasn’t available. Because they weren’t advanced at the time, the opportunity could be lost forever. Consider, if it takes $1 billion to take a new medicine from early research through the regulatory systems (where safety, efficacy and manufacturing standards exist) and then to market, who will pay?

Who will take those risks if there isn’t a return? It is also more than money that’s required. PFROs also need access to additional skills, knowledge and quality systems that are not readily available in institutions. With currently available pathways for translation research needs to become investor ready and be attractive in time for any potential investors to generate a potential return.

Making investments in translation including a good Technology Transfer Office can positively influence culture, encourage researchers to look for translatable opportunities, which will make their work far more relevant and provide opportunities for community benefits to be realised.

When supporting medical research, the following may be useful questions to consider:

1. Do you look beyond quality research to consider the culture, capability and capacity of the PFRO and their systems to support the translation of research in your due diligence?

2. Do you consider the market, competitive advantage, regulatory systems, planning, scale, pathways and other factors relating to the potential for translation in your due diligence when funding research?

3. Can we find new funds or funding models to better resource PFROs enabling translation/commercialisation?

4. If you are a researcher or PFRO should you accept grants without considering intent and your ability translate the outcomes from research?

Whilst Funders of research may not be able to directly fund the administration for translation they have the potential to be more than a band aid solution to an imperfect system where good intent may not be enough. By helping influence culture, by looking at what and how research is funded and by considering intent more closely greater translational outcomes could be realised.

By considering the pathways of research to impact the funder, researcher and PFRO can more effectively identify collaborations that collectively move beyond the status quo.

Join the conversation at NFMRI’s 2019 conference being held in Torquay Victoria, 20-21st November.

Thank you to our conference supporter Phillips Ormonde Fitzpatrick our session sponsor Hall & Wilcox and the many speakers agreeing to participate at this years event.